Design for All: Inclusive Principles

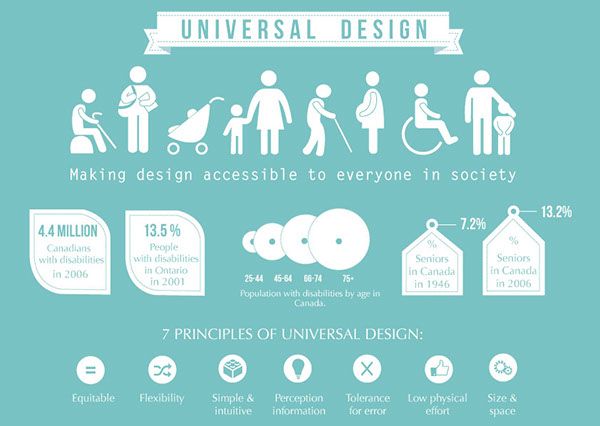

In the modern world, the concept of design is expanding far beyond mere aesthetics or functionality. A crucial paradigm shift is underway, emphasizing that truly effective design must cater to the widest possible range of human abilities, backgrounds, and preferences. This is the essence of inclusive design: creating products, services, and environments that are accessible and usable by everyone, regardless of age, ability, or circumstance. It’s not just a moral imperative but a strategic business advantage, unlocking new markets and fostering innovation. This comprehensive exploration delves into the core principles of inclusive design, its profound impact, its real-world applications, and the vital role it plays in shaping a more equitable and profitable future for companies and creators alike. For content creators focused on SEO and Google AdSense revenue, understanding and articulating the nuances of inclusive design offers a rich vein of high-value keywords and audience engagement.

The Inclusive Design Imperative

At its heart, inclusive design recognizes the vast diversity of human experience. It moves beyond the traditional idea of designing for an “average” user—a notion that inevitably excludes a significant portion of the population. Instead, it proactively considers the needs of individuals with diverse abilities, including those with permanent, temporary, or situational disabilities. This holistic approach ensures that solutions are not just compliant with accessibility standards, but genuinely usable, comfortable, and intuitive for everyone.

The imperative for inclusive design stems from several critical factors:

- Human Rights and Equity: Every individual has the right to access information, services, and opportunities. Design should not be a barrier but an enabler.

- Demographic Shifts: Global populations are aging rapidly. As people live longer, the prevalence of age-related impairments increases, demanding more adaptable designs.

- Market Opportunity: Excluding segments of the population means missing out on significant market share. Designing inclusively opens up products and services to a much larger user base.

- Innovation Catalyst: Constraints often drive creativity. Designing for extreme users often uncovers innovative solutions that benefit everyone, not just those with specific needs.

- Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Many regions have laws and regulations (e.g., ADA in the US, EN 301 549 in Europe) that mandate accessibility, making inclusive design a legal necessity.

- Enhanced Brand Reputation: Companies committed to inclusive design are perceived as more ethical, responsible, and forward-thinking, strengthening their brand image.

Core Principles of Inclusive Design

While often intertwined with accessibility, inclusive design is a broader concept. Accessibility focuses on meeting specific standards for people with disabilities, whereas inclusive design aims to proactively design for diversity from the outset, leading to more broadly usable solutions. Several guiding principles underpin this philosophy:

A. Provide Comparable Experience

This principle dictates that all users, regardless of their abilities, should be able to achieve the same goals and have a similar quality of experience. It means avoiding “separate but equal” solutions, which often lead to inferior experiences for certain groups.

- Equal Access to Information: Ensure information is available in multiple formats (visual, auditory, tactile) so that users can choose their preferred mode of consumption. For example, a video should have captions for the hearing impaired and audio descriptions for the visually impaired.

- Equivalent Functionality: The core functions of a product or service should be available to everyone, even if the interaction method differs. A button that can be clicked by a mouse user should also be navigable via keyboard for a motor-impaired user or activated by voice command for someone unable to use their hands.

- Consistent Quality: The experience shouldn’t feel like a compromise for any user group. The aesthetic appeal, ease of use, and overall satisfaction should be comparable across all interactions.

B. Consider Situational Diversity

Inclusive design recognizes that a person’s abilities can change not only permanently (e.g., blindness) but also temporarily (e.g., broken arm) or situationally (e.g., holding a baby, in a noisy environment, distracted). Designing for these temporary and situational impairments often benefits a much wider audience.

- Temporary Disabilities: Someone with a sprained wrist might temporarily need a keyboard alternative. Good inclusive design addresses this.

- Situational Impairments: Trying to use a phone in bright sunlight (visual impairment), listening to a podcast in a noisy subway (hearing impairment), or navigating an app while carrying groceries (motor impairment). Solutions for these scenarios benefit everyone.

- Cognitive Load: Designing for someone who is distracted or under stress can lead to simpler, clearer interfaces that reduce cognitive load for all users.

C. Offer Choice and Flexibility

People interact with the world in diverse ways. Inclusive design provides multiple ways to achieve a goal, allowing users to choose the method that best suits their preferences, abilities, and context.

- Customizable Interfaces: Allow users to adjust font sizes, color contrasts, spacing, and layouts to fit their visual needs.

- Multiple Input Methods: Support touch, mouse, keyboard, voice, and gesture controls. For example, a smart home device might respond to voice commands, app control, or physical buttons.

- Adjustable Speeds and Timing: Provide options to adjust the speed of animations, audio playback, or time limits for interactions.

- Personalized Experiences: Allow users to save their preferences, ensuring a consistent and tailored experience across sessions.

D. Be Clear and Consistent

Clarity and consistency are paramount in inclusive design. Ambiguity leads to frustration and exclusion.

- Plain Language: Use simple, straightforward language, avoiding jargon or overly complex sentences. Provide clear instructions and feedback.

- Predictable Interactions: Elements should behave in a consistent and predictable manner. If a button looks a certain way, it should always perform a similar action.

- Visual and Functional Consistency: Maintain consistent branding, layout, navigation patterns, and iconography throughout an interface or environment. This reduces cognitive load and aids learnability.

- Error Prevention and Recovery: Design systems that prevent errors where possible, and provide clear, actionable feedback when errors do occur, guiding users to easy recovery.

E. Prioritize Content and Meaning

The core message or function should always be the focus, not just its presentation. Ensure that the content itself is accessible and comprehensible.

- Semantic Structure: Use proper semantic HTML (for web) or logical document structures (for print/digital) to define headings, paragraphs, lists, and images. This allows assistive technologies to interpret content correctly.

- Meaningful Alternatives: Provide descriptive alternative text for images, transcripts for audio, and detailed descriptions for complex visuals. These alternatives ensure that users who cannot perceive the original content still grasp its meaning.

- Hierarchical Information: Organize information logically, using clear headings, subheadings, and progressive disclosure to guide users through complex content.

- Independent of Sensory Characteristics: Do not rely solely on color, shape, size, or location to convey information. Combine these with text labels, patterns, or auditory cues for redundancy.

Real-World Applications of Inclusive Design

Inclusive design is not confined to digital interfaces; its principles are applied across a vast spectrum of industries and products, yielding significant benefits.

A. Digital Products (Websites, Apps, Software)

This is perhaps the most visible area of inclusive design, often overlapping with web accessibility standards like WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines).

- Keyboard Navigation: Ensuring all interactive elements can be reached and operated using only a keyboard. This is vital for users with motor impairments or those using screen readers.

- Color Contrast: Maintaining sufficient contrast between text and background colors for readability, especially for users with low vision or color blindness.

- Scalable Text and Responsive Layouts: Websites and apps that adapt gracefully to different screen sizes and allow users to enlarge text without breaking the layout.

- Screen Reader Compatibility: Structuring content semantically and providing alt text for images so that screen readers can accurately convey information to visually impaired users.

- Form Accessibility: Clear labels, logical tab order, and error messages that are easily understood by assistive technologies.

B. Physical Products and Industrial Design

From everyday objects to complex machinery, inclusive design transforms physical products.

- Ergonomic Design: Products that are comfortable and easy to use for people with varying hand sizes, grip strengths, and dexterity. Examples include easy-to-open packaging, accessible kitchen tools, or adjustable office furniture.

- Universal Controls: Designing buttons, dials, and interfaces that are tactile, clearly labeled (with tactile indicators like braille or raised text), and operable with different levels of fine motor control.

- Sensory Feedback: Providing auditory clicks, haptic vibrations, or visual cues in addition to traditional indicators for confirmation or warnings.

- Adaptive Features: Products with modular components or adjustable settings that can be customized to individual needs, like wheelchairs with adaptable seating or hearing aids with customizable sound profiles.

C. Architecture and Urban Planning

Designing physical spaces with inclusivity in mind creates environments that are truly public and welcoming.

- Ramps and Lifts: Beyond basic code requirements, designing gentle, well-lit ramps and reliable lifts ensures seamless navigation for wheelchair users, parents with strollers, or people with mobility aids.

- Tactile Paving: Textured ground surfaces that provide warning and directional cues for visually impaired pedestrians.

- Clear Signage and Wayfinding: High-contrast, large-print, and well-placed signs with consistent iconography, possibly including braille or audio cues.

- Accessible Restrooms: Spacious stalls, grab bars, lowered sinks, and automatic fixtures.

- Inclusive Playgrounds: Play structures that cater to children of all abilities, including those using wheelchairs or with sensory sensitivities.

- Public Transportation: Buses, trains, and stations designed with level boarding, audible announcements, visual displays, and sufficient space for mobility devices.

D. Services and Customer Experiences

Inclusive design extends to how services are delivered and how customers interact with organizations.

- Diverse Communication Channels: Offering customer support via phone, email, chat, sign language interpreters, or in-person assistance to accommodate various communication preferences and abilities.

- Assisted Shopping Experiences: Providing shopping carts adapted for wheelchair users, or offering staff assistance for those who need help reaching items or navigating stores.

- Accessible Events: Ensuring event venues have accessible entrances, seating, restrooms, and providing accommodations like sign language interpreters or audio descriptions.

- Simple Language in Contracts/Forms: Using plain language to make legal documents, consent forms, and service agreements understandable to a wider audience, including those with cognitive disabilities or limited literacy.

The Business Case for Inclusive Design

Beyond the ethical considerations, there is a compelling business case for embracing inclusive design. It’s not just “nice to have” but a strategic necessity for growth and competitive advantage.

A. Expanding Market Reach

- Disability Market: Globally, over 1.3 billion people experience significant disability. This represents a massive untapped market with substantial spending power. When their families and friends are considered as influencers and purchasers, the market impact quadruples.

- Aging Population: As noted, an aging demographic means more people will experience age-related sensory, cognitive, or physical changes. Designing for them proactively ensures products remain relevant to a growing segment of consumers.

- Situational Users: As previously discussed, designing for temporary or situational needs (e.g., bright sunlight, noisy environment) benefits everyone, leading to broader appeal and greater usability for the general population.

B. Enhancing Innovation and Creativity

- Driving Breakthroughs: Designing for “extreme users” (those with significant impairments) often uncovers fundamental design challenges that, once solved, lead to innovative solutions benefiting all users. For example, remote controls were originally designed for people with mobility impairments, and curb cuts were for wheelchair users, yet both are now universally used.

- Broader Perspectives: An inclusive design process encourages designers to challenge assumptions, think more creatively about different interaction models, and embrace diverse perspectives, leading to richer, more robust solutions.

C. Improving Brand Reputation and Loyalty

- Positive Brand Image: Companies seen as committed to inclusion and accessibility are viewed more favorably by consumers, employees, and stakeholders. This builds trust and goodwill.

- Customer Loyalty: When users feel understood and valued, they are more likely to become loyal customers and advocates for the brand.

- Talent Attraction: A commitment to inclusive design often signals a company culture that values diversity, making it more attractive to top talent, including those with disabilities.

D. Reducing Legal Risks and Costs

- Avoiding Lawsuits: Non-compliance with accessibility laws can lead to costly lawsuits, fines, and reputational damage. Proactive inclusive design mitigates these risks.

- Reduced Rework: Integrating inclusive principles from the start is more cost-effective than retrofitting accessibility features later in the development cycle. “Fixing it in post” is always more expensive.

- Competitive Advantage: Companies that proactively adopt inclusive design can position themselves as leaders, gaining a competitive edge over those who lag in accessibility.

Implementing Inclusive Design: A Practical Approach

Integrating inclusive design isn’t a one-time task; it’s an ongoing process and a mindset shift.

A. Embrace Diversity in Your Team

- Hire Diverse Designers: Ensure your design team includes individuals with varying backgrounds, abilities, and life experiences. This brings inherent diverse perspectives to the design process.

- Involve Users with Disabilities: The “nothing about us without us” mantra is critical. Actively involve people with diverse abilities in user research, testing, and feedback sessions. Their insights are invaluable.

B. Adopt Inclusive Design Principles Early

- Shift Left: Integrate inclusive considerations from the very first stages of ideation and concept development, rather than treating them as an afterthought or a “check-box” at the end.

- Design Guidelines: Develop internal inclusive design guidelines and checklists that team members can follow during the design and development process.

C. Utilize Inclusive Research Methods

- Diverse User Personas: Create user personas that include disabilities, temporary impairments, and situational contexts, helping designers empathize with a wider range of users.

- Accessibility Audits: Regularly conduct accessibility audits using automated tools and manual testing by individuals with disabilities.

- Usability Testing with Diverse Groups: Test prototypes and products with a wide range of users, including those who use assistive technologies.

D. Foster a Culture of Empathy and Awareness

- Training and Education: Provide ongoing training for all staff—designers, developers, marketers, customer service—on the principles of inclusive design and accessibility best practices.

- Empathy Building: Encourage empathy by using simulators (e.g., vision impairment goggles), or by tasking designers to perform common actions using only keyboard navigation or screen readers.

E. Leverage Technology and Tools

- Accessibility Checkers: Use automated tools during development to flag common accessibility issues (e.g., color contrast, missing alt text).

- Assistive Technologies: Familiarize your team with popular assistive technologies like screen readers (JAWS, NVDA, VoiceOver), speech recognition software, and alternative input devices.

- Design System Components: Build accessible components directly into your design system, ensuring that all subsequent designs inherit accessibility features by default.

A World Built for Everyone

The trajectory of design is undeniably towards greater inclusion. As technology advances and societal awareness grows, the expectation will no longer be simply “accessible” but inherently “inclusive.” The future of design is one where:

- Personalization is Key: Products and interfaces adapt seamlessly to individual user needs and preferences without requiring complex manual adjustments.

- AI Plays a Supportive Role: Artificial intelligence will increasingly assist designers in identifying accessibility issues, generating inclusive design alternatives, and even providing real-time feedback during the design process.

- The “Curb Cut Effect” is Amplified: Solutions created for specific accessibility needs will continue to demonstrate unexpected benefits for the general population, leading to more intuitive and robust products for everyone.

- Inclusive Design Becomes the Standard: It will no longer be a specialized field but an intrinsic part of good design practice across all disciplines, from industrial design to digital experience.

Ultimately, inclusive design is more than just a set of guidelines; it’s a profound shift in mindset that places human diversity at the center of the creative process. By embracing this philosophy, designers and businesses can unlock unprecedented innovation, expand their reach, strengthen their brands, and contribute to building a world that truly works for everyone. This commitment to universal usability is not just a trend; it’s the defining characteristic of responsible and effective design in the 21st century.